CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL IN PUEBLO, COLORADO| Narcan is stocked in the same case as a defibrillator and other medical supplies (Pictures/ Parker Seibold – KFF Health News)

THIRD OF COLORADO SCHOOL DISTRICTS RECEIVE NALOXONE FROM THE STATE.

By Rae Ellen Bichell and Virginia García Pivik

Produced by KFF Health News in collaboration with El Comercio de Colorado

Haga click aquí para leer la versión en español

Colorado is one of the states ensuring schools have free or reduced-cost access to the opioid overdose reversal medication naloxone. However, by the start of the school year, most districts had not enrolled in the state distribution program due to the stigma around this life-saving intervention.

In 2022, a student fainted while leaving one of the bathrooms at Central High School in Pueblo, Colorado. When Jessica Foster, the school district’s supervising nurse, heard the young woman’s distraught friends mention drugs, she knew she had to act quickly. First responders were just four minutes away. “But still, four minutes, if they’re not breathing at all, is four minutes too long,” Foster said.

Foster said she obtained a dose of naloxone, a medication that can quickly reverse an opioid overdose, and administered it to the student. The girl revived. 45 miles away in Colorado Springs, officials at Mitchell High School did not have naloxone on hand when a 15-year-old student overdosed in class in December 2021 by snorting a fentanyl pill in a school bathroom. . The young man died.

Jessica Foster, pictured at Central High School in Pueblo, Colorado, is the nurse supervisor for Pueblo School District 60. Last year, Foster administered Narcan to a student who had fallen unconscious in the hallway outside of a school bathroom. (Parker Seibold for KFF Health News)

Program in Colorado

Since then, the Colorado Springs school district has joined Pueblo and dozens of other districts in supplying schools with doses of Narcan, one of the brand names for the life-saving medication. Since passing a state law in 2019, Colorado has had a program that allows schools to get the medication, usually in nasal spray form, for free or at a reduced cost.

However, not all schools agree with this idea. More districts have joined since last year, but only about a third of Colorado districts had signed up for the program for the 2023-2024 school year. Many school districts located in the dozen counties with the highest drug overdose death rates in the state have not signed up.

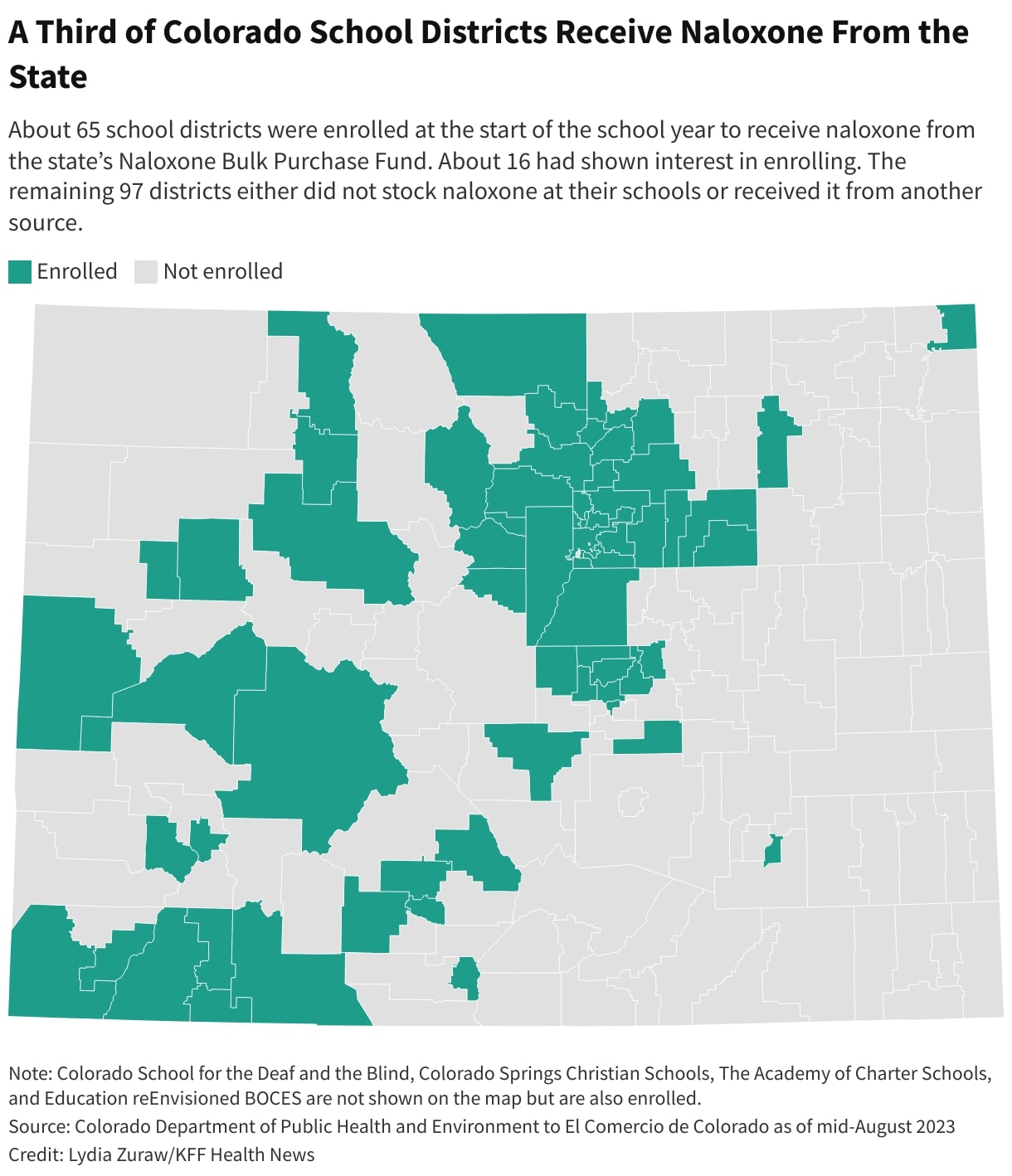

A Third of Colorado School Districts Receive Naloxone From The State

Fear of stigma

According to Kate King, president of the National Association of School Nurses, the reluctance to have it in schools is due to school administrators resisting providing a medical service. The cost of resupplying naloxone and training staff to use it is another issue. But the main obstacle is that schools fear being stigmatized because they have a drug problem. Or they can be identified as schools that tolerate bad decisions.

“School districts are very careful with their image,” said Yunuen Cisneros, director of inclusion and community outreach at the Public Education & Business Coalition, “Many of them do not want to join this program, because accepting it is accepting a drug addiction problem. “We have to equate it to our stock of albuterol for asthma attacks or our stock of epinephrine for anaphylactic shock,” King said.

Some 97 school districts without registering

More Colorado schools have naloxone supplies available for students. “It’s the largest amount we’ve ever had,” said Andrés Guerrero, CDPHE overdose prevention program manager. According to data provided by the Colorado Department of Health, 65 school districts were enrolled in the state program to receive free or low-cost naloxone at the start of the school year.

Another 16 had contacted the state to request information. But by mid-August, orders had not yet been finalized. The remaining 97 school districts either did not have naloxone in their schools or had purchased it elsewhere. Guerrero explained that districts decide who to train to administer the medication. School nurses, teachers and students participate.

DPS and districts with fewer students

The state’s seven largest districts, with more than 25,000 students each, participate in the state program. Instead, only 21 percent of districts with up to 1,200 students have enrolled in the program, even though many of those small districts are in areas with drug overdose death rates higher than the state average.

Denver Public Schools (DPS), Colorado’s largest school district, began stocking naloxone in 2022. “We know that some students are on the front lines of these issues sooner than older generations. Know where to find and access the medication when needed I think it gives them some sense of relief,” said Jade Williamson, DPS Healthy Schools Program Manager.

Victims in Colorado

Colorado health officials could not say how often naloxone had been used in the state’s schools. So far this year, at least 15 young people between the ages of 10 and 18 have died from fentanyl overdoses, but not necessarily in schools. And in 2022, 34 died in that age group, according to the state Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE).

One of the victims was José Hernández, 13, who died at his home in August 2022 from a fentanyl overdose, just days after starting eighth grade at Aurora Hills Middle School. His grandmother found his body one morning, over the bathroom sink.

They demand the right to carry Naloxone

At Durango High School, the 2021 death of a high school student prompted students to demand the right to bring naloxone to school with parental permission—and to administer it if necessary—without fear of punishment. It took organizing a protest during a school board meeting to get the permit, said Hays Stritikus, who graduated this spring from Durango.

Stritikus is now involved in drafting legislation that would expressly allow students across the state to carry and distribute Narcan in schools. “The goal is a world where Narcan is not necessary,” he said. “But unfortunately, that’s not where we live.”

Disagreement

Some health experts disagree that all schools should stock naloxone. Lauren Cipriano, a health economist at Western University in Canada, has studied the effectiveness of naloxone in that country’s high schools. Although opioid poisonings have occurred in schools, she said, high schools tend to be very low-risk environments.

According to Cipriano, the distribution of the medicine must be carried out at needle exchange centers; supervised drug consumption places; and centers for medication-assisted treatment that reduces withdrawal symptoms. “When the state creates a big free program like this. It’s cheap and it looks like you’re doing something, and that’s political gold,” she said.

Get the medicine on your own

Some school districts have found a way to obtain naloxone outside of the state program. This includes Pueblo School District 60, where Nurse Supervisor Foster administered naloxone to a student last year. The Pueblo school district gets free naloxone from a local nonprofit called the Southern Colorado Harm Reduction Association.

Foster said she tried to enroll in the state program but encountered difficulties. So she decided to stick with what was already working. Moffat County RE-1 School District in Craig, Colorado, gets its naloxone from a local addiction treatment center, according to Myranda Lyons, a district nurse. Lyons said she trains school staff on how to administer it when she teaches them CPR.

Christopher deKay, superintendent of the Ignacio 11Jt School District, said his school resource personnel already carry naloxone, but the district also signed up for the state program, so schools can store the medication in the nurse’s office. “You never know what’s going to happen at your school. If the unthinkable happens, we want to be able to respond in the best way possible,” said deKay.

In other areas of the US

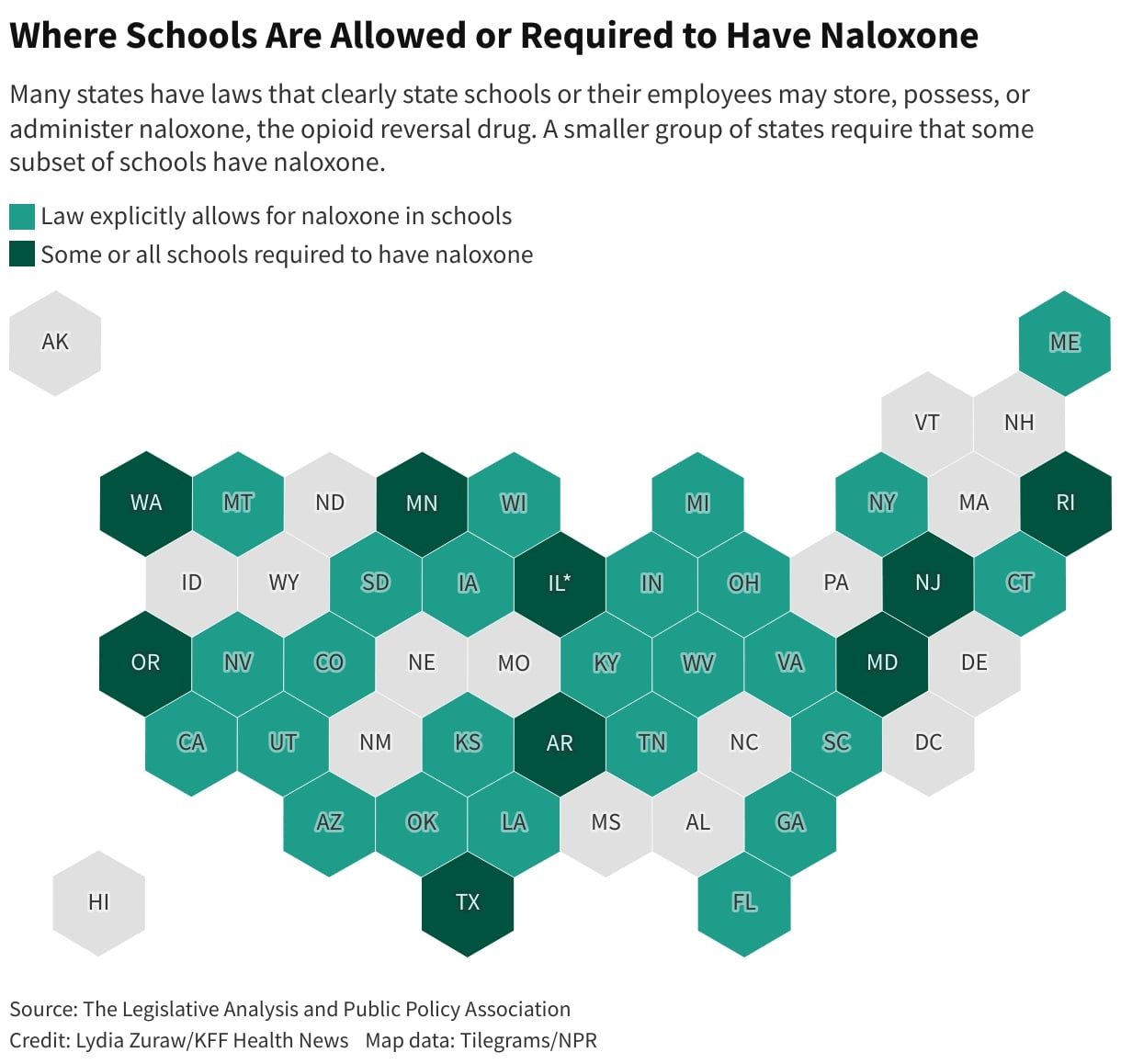

Some 33 states have laws that expressly allow schools or their employees to carry, store or administer naloxone, according to Jon Woodruff, managing attorney for the Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association (LAPPA). About 9 states require some K-12 centers to store naloxone on site, including Illinois, whose rule goes into effect in January.

Some states, such as Maine, also require public schools to offer training to students on how to administer naloxone in nasal spray form. Rhode Island requires all K-12 facilities, both public and private, to stock naloxone. Joseph Wendelken, a spokesman for the Rhode Island Department of Health, said naloxone was administered nine times in educational settings in the past four years.

Non-prescription medication

In early September, the drug also began to be sold without a prescription nationwide. Although the price per two-dose container is $45, addiction specialists have concerns. They fear it is out of reach of those who need it most. But the medication is still not as widely publicly available as fire extinguishers.

You may also like:

Suave Fest, celebrating US Hispanic brewers

Adams County Latino Festival will honor the Hispanic community

Ramiro Cavazos: “Hispanics have a lot to lose with the closure of the federal government”

otras noticias

Digital Calendar – May 2024

COVID-19 Affected Individuals Live with its Effects

The gorillas of AMLO